These days, in-game advertising is the rule, not the exception. According to an Omdia survey, gaming companies around the world raked in over 42 billion dollars in 2019, solely from in-game ads. Free-to-play giants like Genshin Impact and Call of Duty Mobile are largely supported by a combination of ads and high-value in-app purchases.

This isn't a mobile or even a free-to-play phenomenon. EA caught flak last year for displaying the equivalent of pre-roll ads in UFC 4, a full-priced console game. But when did this all start?

When did game developers realize that their medium offered opportunities to monetize through ads? What did the first in-game advertisements look like? In this piece, we'll take a step back and briefly explore the history of in-game advertisements.

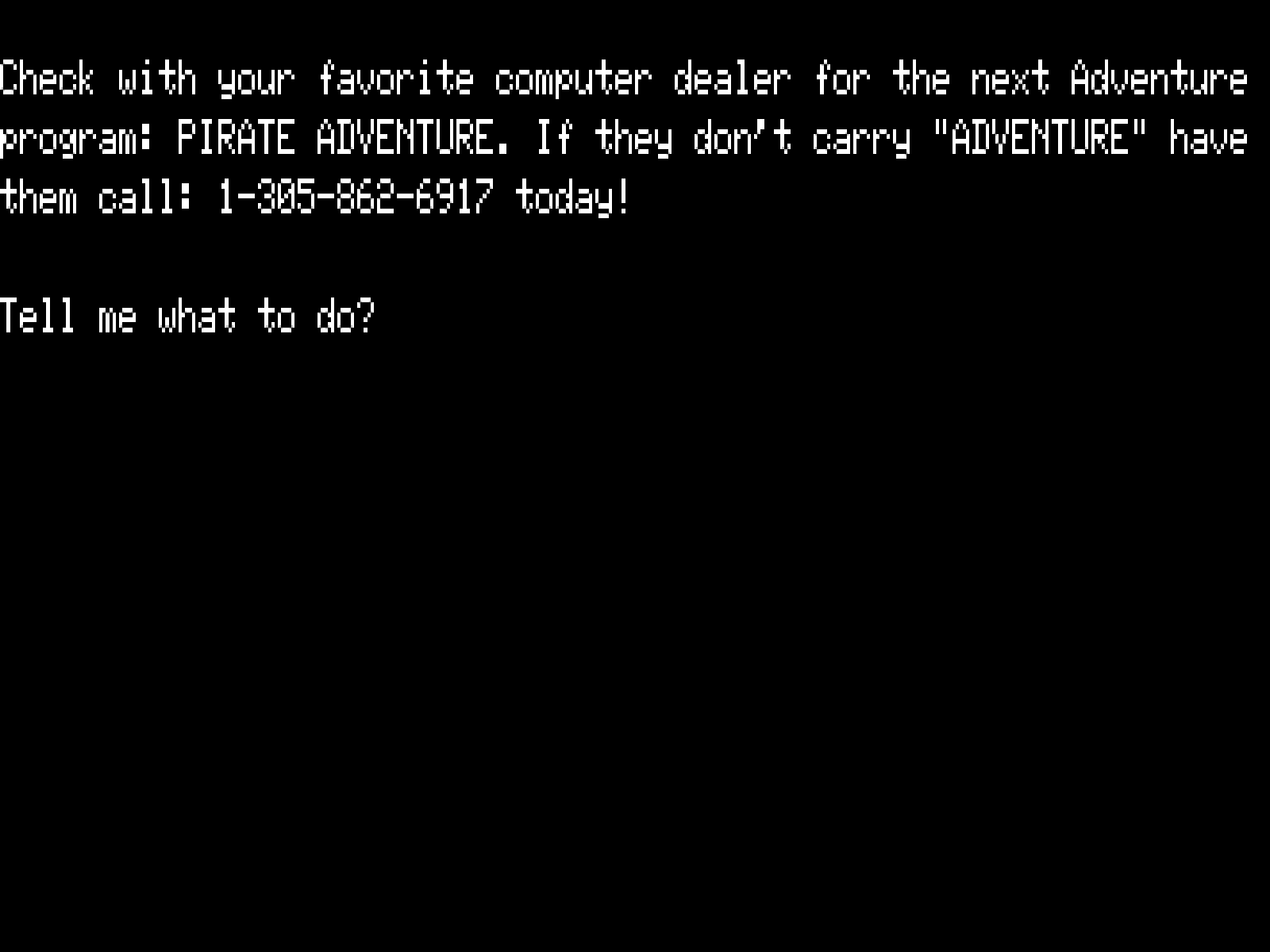

Adventureland: the first ever in-game advertisement

Back in the 1970s, many video games didn't even have visual graphics, let alone space for a full screen ad. But this didn't deter Scott Adams, developer of Adventureland, from placing a brief ad in the game for his next title.

The Pirate Adventure advertisement isn't exactly what comes to mind when you think of in-game ads. There were no graphics since Adventureland was a text-based game. And the ad wasn't for an unrelated product or service: Adams wasn't trying to get you to buy a pair of Yeezys, he was trying to generate awareness for his next project.

The 1980s: the golden age of advergames

A few years after Adventureland, the video game landscape underwent rapid transformation. Through the 1980s, arcade cabinets and home consoles like the NES and Sega Master System saw a surge in popularity. Product placement was commonplace in other forms like TV and cinema at the time. Movies like Back to the Future prominently featured brands like Nike and Pepsi. And so, marketing executives saw video games as fertile new ground for product placement.

The first recorded advergame is "Tapper," from 1983, a game about serving Budweiser beer to bar patrons. Tapper arcade cabinets were often installed in bars. The game's graphics featured a prominent Budweiser logo, highlighting exactly which beer brand was promoting the game.

Image: Doron Grunski

Tapper didn't make inroads into regular arcades in its original form – the Budweiser advertising was construed as promoting alcohol to young people. Instead, a rethemed version named Root Beer Tapper, devoid of beer references, made its way to younger audiences, though no longer in advergame form.

Following the Great Video Game crash in 1983, there was a lull in advergames – and video games in general. However, by the late 80s brands once again started to leverage videogames as a product placement media.

The Ford Simulator, the Pepsi Challenge, and Domino's Avoid The Noid were just a few among a growing number of games where product placement either featured in terms of logos, or as an essential part of the gameplay experience.

The 1990s: new consoles and technical advances

The 90s saw exponential growth in the complexity of video games as developers moved from side-scrollers to full polygonal 3D graphics. Consoles like the Playstation and Nintendo 64, designed around 3D gameplay experiences, along with more capable PCs, opened up new advergaming opportunities.

Remarkably, many of the best 1990s advergames didn't, well, suck. Titles like Chex Quest, a cereal-themed total conversion for Doom were well-reviewed by mainstream gaming media and gamers. The consoles saw their share of advergames, too. Pepsiman, a budget PlayStation title, featured fully 3D graphics, a Pepsi-themed superhero, and plenty of third-person action.

Chex Quest, in particular, is remembered to this day as one of the best advergames ever made. Chex Quest is a total conversion for Doom, swapping out just about every asset in id's game for a more kid-friendly theme. The game features five full levels, and has you playing as the Chex Warrior, on a quest to teleport "Flemoids" back to their home dimension.

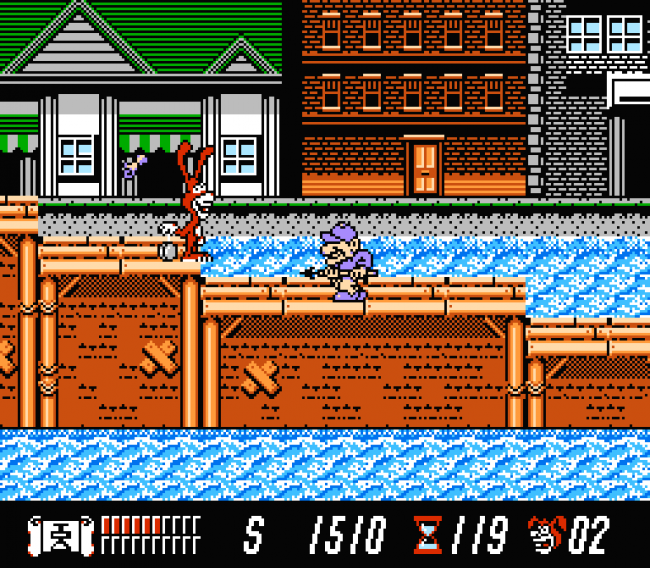

7-Up also got into the advergame action with 1993's Cool Spot and 1994's Spot Goes to Hollywood. These two games featured the red spot on the 7Up logo as the protagonist. The first was a sidescroller that actually received good reviews. Pelit, a Finnish tech magazine, described Cool Spot as "one of the most enjoyable platform games in a long time." Spot Goes to Hollywood, on the other hand, was universally panned for being poorly designed and hard to control.

Cool Spot (the first one) demonstrated that advergames don't necessarily have to be terrible. Because Fido Dido was 7Up's mascot of choice in Europe, Cool Spot was released in European countries with all 7Up branding removed. The favorable Pelit review, then, showed that Cool Spot's gameplay passed muster all on its own.

The 2000s: advergames or games with great product placement?

There's always been a thin line between advergames, explicitly built to promote a particular product, and product placement in-game. From the late 1990s through the mid-2000s, we saw developers partner with brands to integrate real-life products into games with varying degrees of success.

In the best of cases, as with Crazy Taxi on the Dreamcast, product placement aided immersion as players ferried passengers to and from real-world locations, including Levis and Pizza Hut. Such was the case of racing and sports games where in-game adverts enhanced the experience as stadiums and racing tracks were portrayed more realistically if ads were shown as real-life locations.

FIFA and other popular licensed sports franchises made extensive use of in-game product placement and advertising, on billboards, jerseys, and more. The reasoning here was simple: sports events are heavily commercialized with sponsorships, so getting brands into gaming titles like Madden, NHL or NASCAR incurred license fees which, ironically enough, game developers offset by including prominent product placement (just like in real life).

In other cases, bad product placement turned into an immersion breaker. Battlefield 2142, with its Titan mode gameplay, was an innovative multiplayer shooter in many respects. There was one (very) unwelcome innovation, though: digital ad billboards. In a game set 100 years in the future, players had to deal with Pepsi and Intel billboards: a moment spent scratching your head, wondering how a particular ad made sense in Battlefield 2142's world, was often enough to get scoped.

EA, to its credit, understood the drawbacks to this approach and completely removed in-game ads from the Battlefield franchise entry.

The rise of mobile gaming ads

Mobile gaming was a fundamental paradigm shift, both in the way games are designed and how they're consumed. Until recently, console and PC games were mainly sold as physical retail units. Mobile gaming completely upended this system, adding into the mix a larger number of independent development teams. With a variety of in-app advertising options available, in-game ads are often the primary revenue source for mobile game developers.

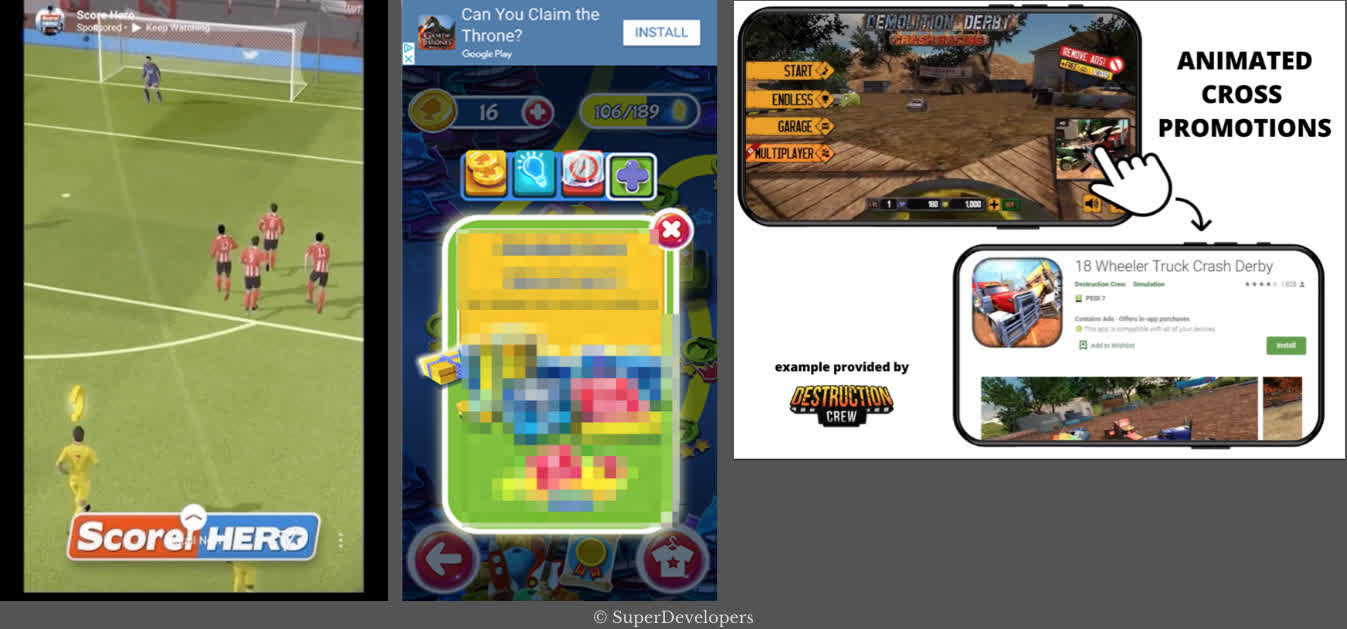

Since the rise of smartphones, in-game advertisements in popular titles have raked in billions of dollars. Over the years, the format and complexity of these have changed significantly. Basic full screen and banner ads were the norm at the beginning. Many free-to-play games would have banners at the top or bottom of the screen, promoting products relevant to individual users. Static, timed fullscreen ads often played in between levels or lives. Video ads are also served at key transition points.

Over this period, in-game became so widespread (and annoying) that it actually had an impact on the way games themselves are developed. Many free-to-play mobile games – including entire genres like endless runners – are built around accommodating ad delivery at frequent intervals. Often, this means designing bite-sized levels, and frequent "death" or lose states: players are then served ads when they lose, and also when they progress.

More recently, ads have become more interactive. In-game ads for free-to-play titles like Homescapes often contain interactive gameplay elements in the advertisement itself: a mini game within the game you're playing. We've also seen brands and artists making virtual appearances in games, like Ariana Grande's Fortnite-only concert.

AR is another area where we're seeing innovation. In titles like Pokemon Go, developers added in-game advertising that made use of real locations, blurring the line between real-world and in-game ads. While mobile is definitely leading the charge these days when it comes to in-game ads, there are plenty of examples to look at in the console and PC space, too.

The Yakuza franchise on PC and console stands out: Yakuza games make extensive use of in-game product placement to create a more believable world: everything from the Don Quijote supermarket to billboard ads for the Nico Nico streaming service have counterparts in real life.

Not all product placement works this seamlessly, however. Take Monster energy drinks in Death Stranding, for example. The ubiquity of Monster in the game, or even how water refills in your canteen turn into the energy drink, are never actually explained. Death Stranding: Director's Cut thankfully gets rid of all Monster references.

In-game advertising is now everywhere. From Adventureland 40 years ago, to Chex Quest and Crazy Taxi, developers have been on the lookout for ways to integrate product placement with games, sometimes for greater "immersion" and others to generate additional revenue. Player interest hasn't always been a top priority, however, advergames and in-game advertising appear to be here to stay.