Sadly, we live in a world where a few individuals have the power to wipe out civilization as we know it with nuclear weapons. We hope that power never gets used, as most of us living things wouldn’t make it far in a radioactive wasteland. Among other hazards, exposure to ionizing radiation has both short- and long-term health effects, thanks to the way it scrambles our DNA.

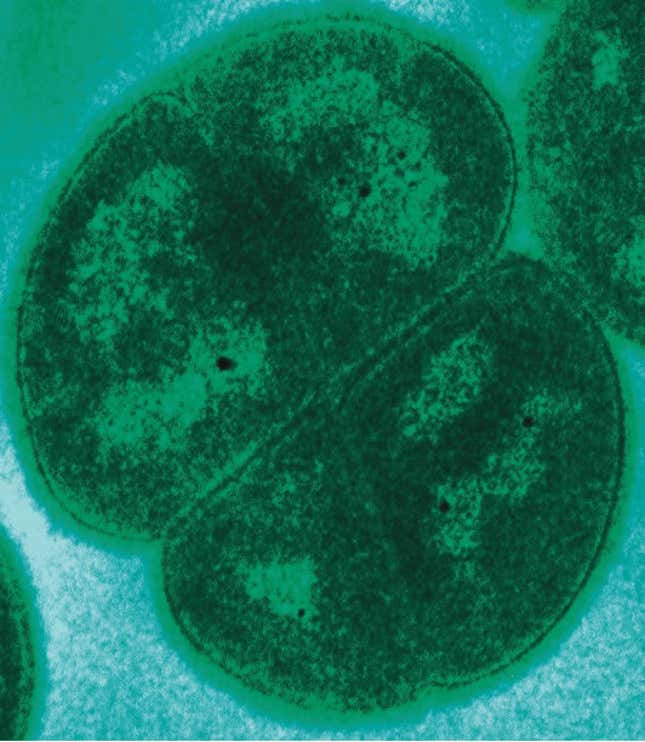

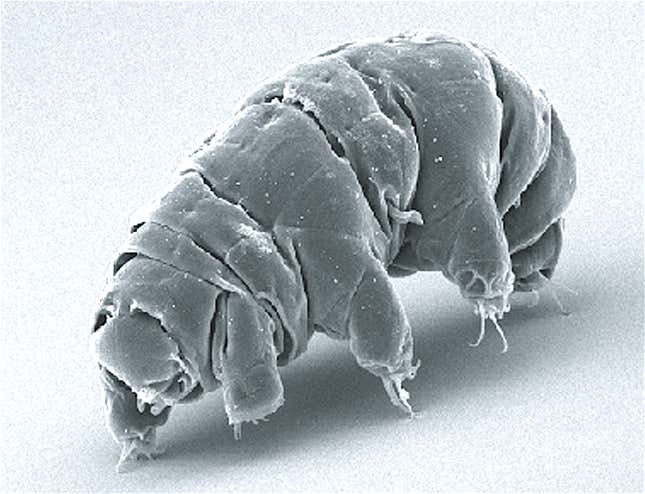

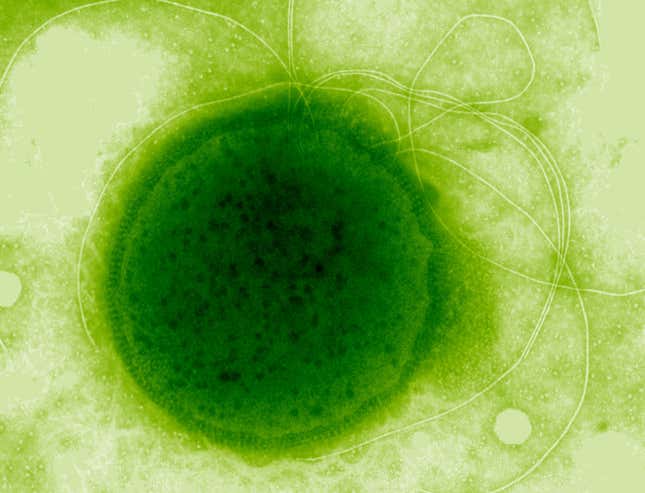

But the world is full of survivors. Some lifeforms have hardly changed over millions of years, while other, newer creature designs have developed out of long, complicated evolutionary processes. When it comes to a post-nuclear world, organisms in both categories stand chances of survival.

This list is made up of species whose radioresistance, or their ability to withstand radiation, has been tested by scientists. None are mammals—the fleshier you are, generally, the less hope you have—but hey, we had a good run.

A version of this story was originally published on January 30, 2021.