When you are in a life-threatening emergency – a serious car accident or having a heart attack or your house is on fire – what do you do? You call 9-1-1, of course. With the emphasis on CALL, because, with just a few exceptions, there’s no other way to get police or firefighter or emergency medical help except calling on the phone. You can’t text 9-1-1 or send an email to a PSAP or tweet to 9-1-1.

When you are in a life-threatening emergency – a serious car accident or having a heart attack or your house is on fire – what do you do? You call 9-1-1, of course. With the emphasis on CALL, because, with just a few exceptions, there’s no other way to get police or firefighter or emergency medical help except calling on the phone. You can’t text 9-1-1 or send an email to a PSAP or tweet to 9-1-1.

9-1-1 Centers, often called PSAPs or Public Safety Answering Points, have a lot of sophisticated technology beyond 1920s-era voice phone calls, but very little of it is used to communicate with the public.

The National Emergency Number Association (NENA) and the government – specifically the Federal Department of Transportation – have a plan to fix that. The plan is called “Next Generation 9-1-1” or NG-9-1-1. At some point you may be able to text 9-1-1 or send an e-mail message or upload photos and video to help first responders protect life and property.

Some cities, however, have already implemented 3-1-1 systems for non-emergency customer service. In these cities – Portland and Denver for examples – you call 9-1-1 for emergencies and 3-1-1 to get help with any other municipal government service such as building permits, streetlight repair or animal control.

I recently did a podcast with Mark Fletcher on the Avaya Podcast Network (APN) discussing 9-1-1, 3-1-1 and these next-generation contact methods for the public. Fletch (@Fletch911) and I came up with the term “Next Generation 3-1-1” to describe using a set of new technologies and social media for citizens to reach their governments for service.

What can NG-9-1-1 and PSAPS learn from “next generation 3-1-1”?

Well, for one thing, “next generation 3-1-1” has already arrived. If you are in one of the places with 3-1-1, you can obviously just call that number to initiate almost any government service or report a problem. But virtually all those 3-1-1 cities also offer a 3-1-1 web input form and give you a tracking number. Some of them now tweet and allow tweeting as an input. Others are experimenting with Facebook pages, online chat, and email. Many of these contact methods allow you to send a photo or video of the issue.

Well, for one thing, “next generation 3-1-1” has already arrived. If you are in one of the places with 3-1-1, you can obviously just call that number to initiate almost any government service or report a problem. But virtually all those 3-1-1 cities also offer a 3-1-1 web input form and give you a tracking number. Some of them now tweet and allow tweeting as an input. Others are experimenting with Facebook pages, online chat, and email. Many of these contact methods allow you to send a photo or video of the issue.

Another common contact method is texting – there’s even “an app for that” in Textizen, developed by Code for America. In truth, Textizen is as much about citizen engagement and interaction as it is 3-1-1 and requesting service. But the important point is that Philadelphia, Austin, Salt Lake City and other places have implemented it as an alternate contact method.

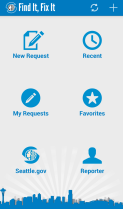

A final, powerful, “NG3-1-1” technology is the downloadable mobile app. Some cities have developed their own app such as Boston’s Citizen Connect or Seattle’s Find It Fix It. These are sometimes built on technology developed by private companies such as Connected Bits or See-Click-Fix (Ben Berkowitz, the CEO, is a worldwide leader in this space).

A final, powerful, “NG3-1-1” technology is the downloadable mobile app. Some cities have developed their own app such as Boston’s Citizen Connect or Seattle’s Find It Fix It. These are sometimes built on technology developed by private companies such as Connected Bits or See-Click-Fix (Ben Berkowitz, the CEO, is a worldwide leader in this space).

A frequent criticism of NG-3-1-1 services and apps is that they only work in one city. You can download the “Chicago Works” NG-3-1-1 app, but cross into the suburbs and it is useless. But Boston and Massachusetts fixing this by extending Boston’s Citizens Connect into Massachusetts Commonwealth Connect. This allows 40 cities in Massachusetts to have their own individually branded app, but, using the GPS feature on smartphones, to report problems no matter where they are. A resident of Chelsea who is in Boston for a Red Sox game could see a problem – a smashed stop sign for example – and use the Chelsea app to report it to the Boston.

Admittedly, we have a long way to go with 3-1-1 – most places in the nation don’t have it (indeed, even in Boston and Seattle you don’t call 3-1-1, but rather a 10 digit phone number). But we can still think about some future “next generation” features for 3-1-1 which would be relatively easy to implement with today’s technology even if they are still difficult to implement in the culture of government operations:

- Fedex-style tracking of service requests. With tracking you could snap a photo of graffiti, get a tracking number and then be notified as the service request is reviewed, triaged, sent to the police department for review by the gang unit, sent to “graffiti control central” to determine if it is on government property and which department (transportation, parks, etc.) is responsible to clean it up, see when the crew is dispatched, be notified when the work is done, and then be asked your opinion of how well the whole process worked. (Some 3-1-1 apps purport to do this now, e.g. Chicago, and the Open 3-1-1.org organization actually is evangelizing it).

- 3-1-1 Open Data and analysis. The details and results of 3-1-1 calls for service should be on an open dataset for anyone to review and, indeed, are in some cities such as Boston, New York City, and San Francisco. Certainly departments and Mayor’s Offices should be analyzing the tracking data to improve service management processes. But how about mashing the 3-1-1 data up against datasets such as building code violations, utility shutoff due to non-payment or crime incident reports to find “hot spots” of difficulties in the City which need to be broadly addressed by cross-functional teams from law enforcement, code enforcement, social workers and more. Boston is, indeed, doing this, but I’ve not been able to find detailed data about it. (Note: Socrata, headquartered in Seattle, is the software driving all the “open data” sites mentioned above as well as hundreds of others such as the Federal Governments own data.gov.

- Facetime and Skype to 3-1-1, conveying video to the 3-1-1 operator so they can see your situation or you can show them graffiti, a problem in the street, and so forth.

- Chat and video chat. Chat functions are fairly common on private customer service sites but extraordinarily rare in government. Indeed, I can’t cite a single example. I think government customer service departments are concerned about being overwhelmed by work if chat is opened to the public.

- Twitter and Facebook comments/apps. Elected officials certainly realize the power of Twitter and Facebook. And I think they (or their staff) actually review and respond to comments or tweets, and even turn them into service requests for follow up. But most of the line departments in most cities (water, transportation, public works, certainly police and fire) don’t accept calls for service via these social media channels. I’d also like to see developers write Facebook apps or games which could be used inside that social media community to engage the public or manage 3-1-1/service requests.

Lessons for NG-9-1-1. I’ve laid out a long list of examples and suggestions above which, together, could be called the “landscape and roadmap” for Next Generation 3-1-1. Some of them clearly could be adopted for use in PSAPs and 9-1-1 centers. The “low hanging fruit” here, I think, for NG 9-1-1 is:

- A smartphone app for texting 9-1-1. Although you can directly text 9-1-1 from your phone, an app would be better because it could prompt you for critical information such as your location. Textizen could be an NG-3-1-1 model for this.

- A smartphone app for calling 9-1-1. This sort of app might not just telephone 9-1-1, but also allow you to include photos or other data from your phone, including GPS coordinates, direction and speed of travel etc.

- Facetime or Skype to 9-1-1. Such an app (when PSAPs are able to receive the information) would allow the telecommunicator in the PSAP to see what’s happening to you or in your area.

A number of obstacles remain, however:

- Technology is an obstacle, as most 9-1-1 centers don’t have even text messaging available, much less email, twitter or chat. A notable exception: York County, Virginia, where past APCO president Terry Hall directs the 9-1-1 center – you can text 9-1-1 in York County.

- Culture and training are an obstacles. Telecommunicators (call takers and dispatchers) in 9-1-1 centers know their jobs extraordinarily well and execute them almost flawlessly, as you hear from tapes after any major incident. Every new technology or method of communication we add to the PSAP makes those jobs harder in terms of training and obtaining the right information to get first responders to the incident.

- Chain of evidence. When a video or video call or image is sent from a citizen to a 9-1-1 center about a crime, can it be used as evidence? Has it been altered (even by Instagram) thereby perhaps rendering it useless in a court of law?

- Security and cybersecurity. We’ve seen cases of “spoofing” telephone numbers and “swatting”, where 9-1-1 centers are tricked into sending officers or SWATs to unsuspecting citizens. Every new method of communicating adds new difficulties in verifying caller identities and preventing such antics.

And, most importantly, with 9-1-1 lives are often at stake, so thorough research and preparation must precede adoption of these new technologies in PSAPs.

My podcast with Mark Fletcher on the Avaya Podcast Network was a fortuitous meeting. We’ve probably coined the phrase “Next Generation 3-1-1”. But while the tools and technologies of NG-3-1-1 certainly chart a path for PSAPs and NG-9-1-1, following that path will require innovative solutions to a number of obstacles.

Excellent blog Bill. It was a real honor to be sitting across from you when we both had the epiphany of NG3-1-1 at the same time during our conversation before the podcast! Thanks for memorializing that discussion in such great detail. Does this make us the parents of NG3-1-1?!

Fletch

I think it does make us “parents” of NG3-1-1. We were there at the “birthing”. Thanks again for having me on your podcast!

Great article Bill and enjoyed listening to the Podcast Mark! I learned something new about NG 9-1-1 and NG 3-1-1…looking forward to hear more abouth the development and growth of NG 3-1-1.