Employers Must Navigate Social-Values-Based Branding With Care

Social Values, Employer Branding, And Econ 101

The role of social values in motivating consumer behavior is a topic that gets a lot of attention. We’ve even built an econometric model to identify and size consumer segments with the greatest likelihood to purchase based on social considerations. What is not as readily apparent is the role of social values in shaping employee behavior, both in choice of workplace and in the depth of engagement.

Just as marketers are shoring up their social purpose programs to address consumer demand, they must consider the same on the home front with their employees. But employer branding based on social values is a whole different kettle of fish. Consumers don’t care much about most brands they interact with, but employees’ identities are inseparable from their employers. What a company values and how those values translate into behavior will disproportionately impact how employees perceive the brand.

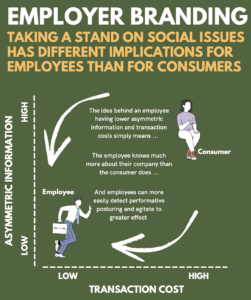

To explain why value-based brand building differs for consumers and employees, let’s borrow two concepts from Econ 101: asymmetric information and transaction costs.

Asymmetric Information

It’s just what it sounds like: In a transaction between two parties, sometimes one knows a lot more than the other and can take (often unfair) advantage of that asymmetry, such as a used car seller who knows much more about the car they are selling than most hapless buyers and can get away overpricing the vehicle. It’s a simple idea but one that has proved worthy of a Nobel Prize.

Transaction Costs

The meaning here is also quite literal: Transaction costs are the costs associated with conducting a transaction but separate from what you pay for the goods and services (for example, a broker’s fee). In the context of asymmetric information, you can think of this as the cost associated with reducing the asymmetry. For instance, you pay a mechanic to check out the used car to reduce the chances of being hoodwinked.

Customers, Employees, And Asymmetry Differentials

In dealing with companies, customers and employees have significantly different information asymmetries. Let’s work through an example: You want to buy coffee beans hailing from the fecund slopes of Guatemalan volcanoes. But you are concerned about labor practices and fair wages, so you look for a brand with assurances that you are buying responsibly. But can you be so sure? No matter how many macchiatos you’ve downed, you probably don’t understand the complex coffee supply chain and how the brand sources the beans. You are not privy to the information that the manufacturer possesses (asymmetric information). You’d hope the brand is on the up and up, but we have seen far too many instances of child labor, emissions fraud, and carcinogenic consumer products to be that gullible.

Can you reduce this information asymmetry and unearth every morsel of knowledge about these coffee beans? Sure, but it will cost you inordinate time and resources (transaction costs) to do so and will likely not be worth it. (If someone says the internet has changed all of that with its bounty of knowledge, don’t believe a word of it. A haystack of data with a needle of information is no better than zero information when you have to make a quick decision.) When you consider the number of varied purchase decisions that consumers make daily, you realize that a degree of asymmetry is not just inevitable but optimal.

And The Punchline …

Employees don’t operate behind the same veil of asymmetry; they are in the belly of the beast. They know or can find out (at very low “transaction costs”) about purchasing agreements, labor practices, and just about anything to do with the entire value chain works. Employees motivated by values such as fair working conditions, empowerment, and poverty alleviation can get a far more accurate assessment of their employer’s track record than a consumer can of a brand’s. Knowledge empowers employees, and they wield this power to get their way, like at a prominent PR firm that had to drop an immigration detention center client in response to an employee outcry.

What This Means For Employer Branding

As marketers get ready to embrace an expanded remit to address employer branding and deepen their involvement in employee experience, they must realize that “marketing” to employees is somewhat different. Taking a stand on social issues will entail much more than messaging and positioning. It will require a commitment that the employer must honor through each and every one of the million moments of brand interaction that define the employer-employee relationship.

We have kicked off our employer-branding research workstream and anticipate having several deliverables over the course of 2022, beginning with a flagship research report in late Q1/early Q2. As we work toward that report, you’ll hear from me often, sharing insights that we uncover along the way. So stay tuned for more.